No edit summary |

|||

| Line 166: | Line 166: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

| − | |||

| − | {{Herzegovina-Neretva Canton}} |

||

| − | {{Political divisions of Bosnia and Herzegovina}} |

||

{{coord|43.650|N|17.967|E|display=title|source:dewiki}} |

{{coord|43.650|N|17.967|E|display=title|source:dewiki}} |

||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[bs:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[bg:Кониц]] |

||

| − | [[cs:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[da:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[de:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[fr:Konjic (Bosnie-Herzégovine)]] |

||

| − | [[hr:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[it:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[nl:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[pl:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[sr:Коњиц]] |

||

| − | [[sh:Konjic]] |

||

| − | [[sv:Konjic]] |

||

[[Category:Herzegovina-Neretva Canton]] |

[[Category:Herzegovina-Neretva Canton]] |

||

[[Category:Neretva River]] |

[[Category:Neretva River]] |

||

Revision as of 06:29, 6 March 2011

Konjic is a town and municipality in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is located in northern Hercegovina, around 50 kilometres south-west of Sarajevo. It is a mountainous, heavily wooded area, and is 268m above sea level. The municipality extends on both sides of the Neretva River. The town of Konjic, housed about a third of the total municipality population. Today the population of Konjic municipality is estimated at 39,000 people.

Natural heritage

Neretva river

- Main article: Neretva

Yet another distinctive feature of the Neretva, Stara kamena Ćuprija (Old Stone Bridge) at the town of Konjic. Rebuilt just recently after distruction at the end of WWII.

The Neretva is largest karst river in the Dinaric Alps in the entire eastern part of the Adriatic basin, which belongs to the Adriatic river watershed. The total length is 230 km, of which 208 km are in Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the final 22 km are in the Dubrovnik-Neretva County of Croatia[1][2]. Konjic municipality include, at least, half of the area of Upper Neretva (Template:Lang-bs), which is upper course of the Neretva river. Geographically and hydrologically the Neretva is divided in three section[2]. The upper course of the Neretva river is simply called the Upper Neretva (Template:Lang-bs), and includes vast area around the Neretva, numerous streams and well-springs, three major glacial lakes near the very river (and even more lakes, outside the municipality of Konjic, scatered across the mountains of Treskavica and Zelengora in wider area of the Upper Neretva), one artificial Jablaničko lake, mountains, peaks and forests, flora and fauna of the area. All this natural heritage thogether with cultural heritage of Upper Neretva, representing rich and valuable resources of Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as Europe. The upper course of Neretva, Upper Neretva (Template:Lang-bs) has water of Class I purity[3] and is almost certainly the coldest river water in the world, often as low as 7-8 degrees Celsius in the summer months.

Rakitnica river

- Main article: Rakitnica

Untouched canyon of the Rakitnica river, main tributary of the Neretva at Upper Neretva section.

Rakitnica is the main tributary of the first section of the Neretva river known as Upper Neretva (Template:Lang-bs). The Rakitnica river formed a 26 km long canyon , of its 32 km lenght, that stretches between Bjelašnica and Visočica to southeast from Sarajevo.[4] From canyon, there is a hiking trail along the ridge of the Rakitnica canyon, which drops 800m below, all the way to famous village of Lukomir. Village is the only remaining traditional semi-nomadic, Bosniak, mountain village in Bosnia and Herzegovina. At almost 1,500m, the village of Lukomir, with its unique stone homes with cherry-wood roof tiles, is the highest and most isolated mountain village in the country. Indeed, access to the village is impossible from the first snows in December until late April and sometimes even later, except by skis or on foot. A newly constructed lodge is now complete to receive guests and hikers.

Boračko lake

- Main article: Boračko lake

Blatačko lake

- Main article: Blatačko lake

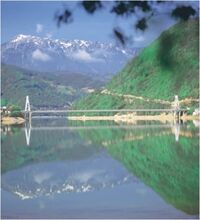

The Neretva distinctive feature, suspension bridge over the Jablaničko Lake at the village of Ostrožac.

Jablaničko lake

- Main article: Jablaničko Lake

Jablaničko Lake (Template:Lang-bs) is a large artificially formed lake on the Neretva river, right below Konjic where the Neretva briefly expanding into a wide valley. Rivere provided lot of fertile, agricultural land there, before lake flooded most of it. The lake was created in 1953 after construction of high gravitational a hydroelectric dam near Jablanica in central Bosnia and Herzegovina. The lake has an irregular enlongated shape. Its width varies along its length. The lake is a popular vacation destiation in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Swimming, boating and especially fishing are popular activities on the lake. There are 13 types of fish in the lake's ecosystem. Many weekend cottages hae been built along the shores of the lake.

Prenj mountain

Endemic and endangered species

Trouts

Neretvanska Mekousna - Neretva's Softmouth trout (Salmo obtusirostris oxyrhynchus).

Glavatica - Marble trout (Salmo marmoratus).

Zubatak trout (Salmo dentex).

The river Neretva and its tributaries represent the main drainage system in the east Adriatic watershed and the foremost ichthyofaunal habitat of the region. Salmonidae fishes from the Neretva basin show considerable variation in morphology, ecology and behaviour. Neretva also has many other endemic and fragile life forms that are near extinction. Among most endangered are three endemic species of Neretva trout: Neretvanska Mekousna (Salmo obtusirostris oxyrhynchus)[5], Zubatak (Salmo dentex)[6] and Glavatica (Salmo marmoratus)[7].

All three endemic trout species of Neretva are endangered mostly due to destruction of the habitat and hybridisation with introduced trouts and illegal fishing as well as poor management of water and fisheries (dams, overfishing, mismanagement)[8][9].

Ecology and protection

Protected area

Dam problems

- Main article: Environmental concerns with electricity generation

The benefits brought by dams have often come at a great environmental and social cost[10][11][12], as dams destroy ecosystems[13] and cause people to lose their homes and livelihoods.

The Neretva and two main tributaries are allready harnessed, by four HE power-plants with large dams on Neretva, one HE power-plants with major dam on the Neretva tributary Rama, and two HE power-plants with one major dam on the Trebišnjica river, which is considered as part of the Neretva watershed.

Also, the government of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina entity has unveiled plans to build three more hydroelectric power plants with major dams (as over 150.5 meters in height)[14] upstream from the existing plants, beginning with Glavaticevo Hydro Power Plant in the nearby Glavatičevo village, then going even more upstream Bjelimići Hydro Power Plant and Ljubuča Hydro Power Plant located near the villages with a same names; and in addition one more at the Neretva headwaters gorge, near the very source of the river in entity of Republic of Srpska by its entity government. This, if realized, would completely destroyed this jewel among rivers, so its strongly opposed and protested by numerous environmentalist organizations and NGO's, domestic[15] as well as international[16][17][18], who wish for the canyon, considered at least beautiful as the Tara canyon in Bosnia and Herzegovina and nearby Montenegro, to remain untouched and unspoiled, hopefully protected too[19][20].

Moreover, the same Government Of FBiH prepering a parallel plan to form a huge National Park which include entire region of Gornja Neretva (Template:Lang-en), and within Park those three hydroelectric power plants, which is unheard in the history of environmenatal protection. The latest idea is that the park should be divided in two, where the Neretva should be excluded from both and, in fact, become the boundary between parks.

This is a cuning plan of engineers and related ministry in Government Of FBiH and should leave the river available for the construction of three large dams, and give them hope in order to remove the fear of contradiction in the plans for environmental protection in the area and the flooding its very heart, in terms of natural values - the Neretva. Of course, such deception failed, because the concerned citizens from the local community are not given bluff, as well as concerned citizens of whole country, and its particularly strongly opposed by NGOs and other institutions and organizations that are interested in establishing the National Park of Upper Neretva towards the professional and scientific principles and not according to the needs of electric energy lobby[21][11][22].

Vajont Dam disaster

- Main article: Vajont Dam

History

The area near the town is believed to be settled up to 4000 years ago, and settlements around 2000 years ago by Illyrian tribes travelling upstream along the Neretva River have been found[23]. Konjic was earliest recorded by name in the records of the Republic of Ragusa (modern-day Dubrovnik in Croatia) on June 16, 1382 [24]. The town, being part of the Bosnian kingdom, was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire, of which the lasting feature for the town (apart from the many mosques and bringing of Islamic faith) is the Ottoman-inspired bridge which features in the town coat of arms, and later into the Austro-Hungarian empire.

During World War II, the town became part of the Independent State of Croatia, and following the war joined the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The town grew significantly and prospered as a vibrant, multi-ethnic city with good transport links (the town is on the railway between Sarajevo and the Adriatic Sea), the large Igman ammunition factory and Yugoslav Army barracks. These factors became one of the main reasons for the conflict in the 1990s.

During the Bosnian War

During conflict in Yugoslavia, Konjic municipality was of strategic importance as it contained important communication links from Sarajevo to southern Bosnia and Herzegovina. During the siege of Sarajevo the route through Konjic was of vital imortance to the Bosnian government forces. Furthermore, several important military facilities were contained in Konjic, including the Igman arms and ammunition factory, the JNA Ljuta barracks, the Reserve Command Site of the JNA, the Zlatar communications and telecommunications centre, and the Celebici barracks and warehouses.

Although the Konjic municipality did not have a majority Serb population and was not part of the declared "Serb autonomous regions", in March 1992, the self-styled "Serb Konjic Municipality" adopted a decision on the Serbian territories. The SDS, in co-operation with the JNA, had also been active in arming the Serb population of the municipality and in training paramilitary units and militias. According to Dr. Andrew James Gow, an expert witness for the Prosecution, the SDS distributed around 400 weapons to Serbs in the area.

Konjic was also included in those areas claimed by the HDZ in Bosnia and Herzegovina as part of the "Croatian Community of Herceg-Bosna", despite the fact that the Croats did not constitute a majority of the population there either. The Croatian Army units (known as the HVO) were established and armed in the municipality by April 1992.

Following the international recognition of the independent Bosnian state and the walk-out of SDS representatives from the Municipal Assembly a War Assembly was formed to take charge of the defence of the municipality. Between 20 April and early May 1992 Bosnian government forces seized control over most of the strategic assets of the Municipality and some armaments. However, Serb forces controlled the main access points to the municipality, effectively cutting it off from outside supply. Bosniak refugees began to arrive from outlying areas of the municipality expelled by Serbs, while Serb inhabitants of the town left for Serb-controlled villages according to the decision made by Serb leadership.[25]

On 4 May 1992, the first shells landed in Konjic town, fired by the JNA and other Serb forces from the slopes of Borasnica and Kisera. This shelling, which continued daily for over three years, until the signing of the Dayton Peace Agreement, inflicted substantial damage and resulted in the loss of many lives as well as rendering conditions for the surviving population even more unbearable. With the town swollen from the influx of refugees, there was a great shortage of accommodation as well as food and other basic necessities. Charitable organisations attempted to supply the local people with enough food but all systems of production foundered or were destroyed. It was not until August or September of that year that convoys from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) managed to reach the town, and all communications links were cut off with the rest of the State. A clear priority for the Konjic authorities was the de-blocking of the routes to Sarajevo and Mostar. This objective required that the Serbian forces holding Bradina and Donje Selo, as well as those at Borci and other strategic points, be disarmed. This objective required that the Serbian forces holding Bradina and Donje Selo, as well as those at Borci and other strategic points, be disarmed. Initially, an attempt was made at negotiation with the SDS and other representatives of the Serb people in Bradina and Donje Selo. This did not, however, achieve success for the Konjic authorities and plans were made for the launching of military operations by the Joint Command.[26]

The first area to be targeted was the village of Donje Selo. On 20 May 1992 forces of the TO and HVO entered the village. Bosnian government soldiers moved through Viniste towards the villages of Cerići and Bjelovcina. Cerići, which was the first shelled, was attacked around 22 May and some of its inhabitants surrendered. The village of Bjelovcina was also attacked around that time. According to witnesses heard by the ICTY, the Serb-populated village of Bradina was shelled in the late afternoon and evening of 25 May and then soldiers in both camouflage and black uniforms appeared, firing their weapons and setting fire to buildings. Many of the population sought to flee and some withdrew to the centre of the village. These people were, nonetheless, arrested at various times around 27 and 28 May, by TO, HVO and MUP soldiers and police.[27]

These military operations resulted in the arrest of many members of the Serb population and it was thus necessary to create a facility where they could be imprisoned and questioned about their role in war crimes during the siege of Konjic. The former JNA Čelebići compound was chosen out of necessity as the appropriate facilities for the detention of prisoners in Konjic. The majority of the prisoners who were detained between April and December 1992 were men, captured during and after the military operations at Bradina and Donje Selo and their surrounding areas. At the end of May, several groups were transferred to the Čelebići prison-camp from various locations. In its judgement in the Delalić case the ICTY found that some Serb prisoners had been beaten, tortured and several murdered by the camp guards, and two women at the camp had been raped (one of them Grozdana Cecez, identity of other woman is unknown). After these information the prison was closed according to the decision of Bosnian government in December 1992 and remaining prisoners released.[28]

Ethnic distribution

1971

40.879 total

- Muslims - 21.599 (52,83%)

- Croats - 12.034 (29,43%)

- Serbs - 6.669 (16,31%)

- Yugoslavs - 202 (0,49%)

- others - 375 (0,94%)

1991

According to the 1991 census, the municipality of Konjic had 43,878 residents: 23,815 Bosniaks (54.3%), 11,513 Croats (26.2%), 6,620 Serbs (15.1%), and 1,930 others (4.4%).[29]

1997

It is estimated that in 1997 there were 32,000 residents: 92,7% Bosniaks, 4,7% Croats, 2,4% Serbs, and 0,2% others.Template:Fact

2005

In 2005, 92% of population of the municipality were ethnic Bosniaks.Template:Fact

Famous people

- Zulfikar Zuko Džumhur - bohemian in nature was a Bosnian documenters-film maker, writer, painter and caricaturist.

- Lazar Drljaća - the last of the Bogumils of Bosnia and famous Bosnian painter;

- Ante Marković - the last prime minister of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

- Ante Pavelić - The Croatian Ustashi Poglavnik of the Independent State of Croatia and World War II war criminal was born near Konjic in 1889.

Also read

Water bodies

|

Settlements

|

Protected environment and tresures

|

Nature and culture

|

Twin cities

- Template:Flagicon Strängnäs, Sweden

External links

- Municipal Website of Konjic Template:Bs icon

- Website of Konjic Template:Bs icon Template:En icon

Template:Commons

References

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Template:Cite web Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Hydro-meteorological institute of Federation of B&H" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ BHTourism - Rakitnica

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Environmental Impact of Dams

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Silenced Rivers: The Ecology and Politics of Large Dams, by Patrick McCully, Zed Books, London, 1996

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Bosna i Hercegovina ...::: Informativno-turisticki portal BiH :::... KONJIC

- ↑ http://www.herceg-tourism.com/towns/konjic.htm

- ↑ Judgement ICTY vs Delic et al., 16 November 1998 [1]

- ↑ Judgement ICTY vs Delic et al., 16 November 1998 [2]

- ↑ Paragraphs 138-139, Judgement ICTY vs Delic et al., 16 November 1998 [3]

- ↑ Paragraphs 141-157, Judgement ICTY vs Delic et al., 16 November 1998 [4]

- ↑ Paragraph 121, Judgement ICTY vs Delic et al., 16 November 1998 [5]

Template:Coord